Doug_Nightmare

Active member

Volokh said:[This month, I'm serializing my 2003 Harvard Law Review article, The Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope; …

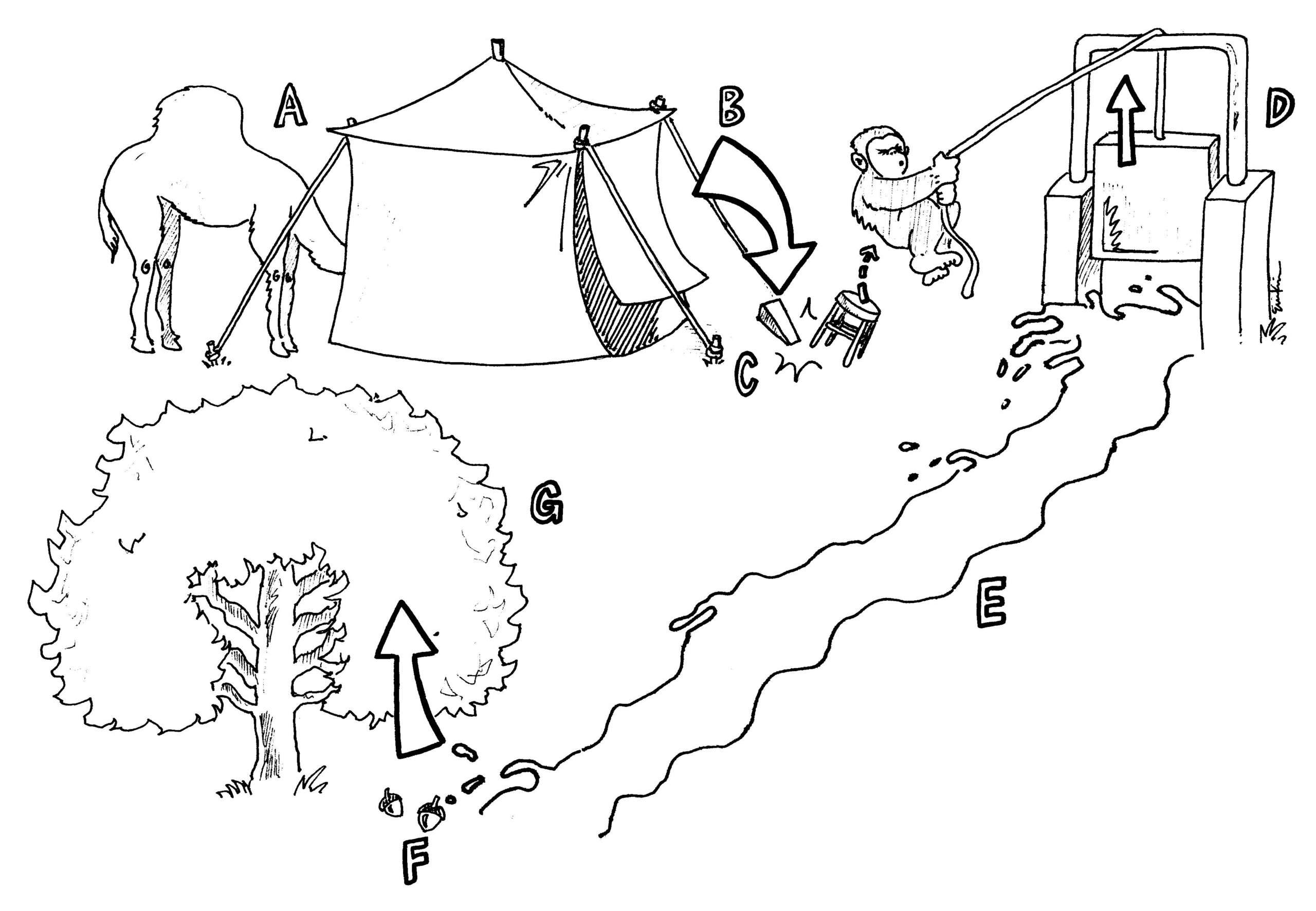

[1.] An Example.—Let's begin with the slippery slope question mentioned in the Introduction: does it make sense for someone to oppose gun registration (A) because registration might make it more likely that others will eventually enact gun confiscation (B)? A and B are logically distinguishable, but can A nonetheless help lead to B?

Today, when the government doesn't know where the guns are, gun confiscation would require searching all homes, which would be very expensive; relying heavily on informers, which may be unpopular; or accepting a probably low compliance rate, which may make the law not worth its potential costs. And searching all homes would be both financially and politically expensive, since the searches would incense many people, including some of the non-gun-owners who might otherwise support a total gun ban.

But if guns get registered, searching the homes of all registrants who don't promptly surrender their guns would become both financially and politically cheaper, especially if a confiscation law bans just one type of gun, covers only a region where guns are already fairly uncommon, or perhaps covers only a subset of the population (such as public housing residents). Confiscation has eventually followed gun registration in England, New York City, and Australia. While it's impossible to be sure that registration helped cause confiscation in those cases, it seems likely that people's compliance with the registration requirement would make confiscation easier to implement, and therefore more likely to be enacted. And Pete Shields, founder of the group that became Handgun Control, Inc., openly described registration as a preliminary step to prohibition, though he didn't describe exactly how the slippery slope mechanism would operate.

Under some conditions, then, legislative decision A may lower the cost of making legislative decision B work, thus making decision B cost-justified in the decisionmakers' eyes. There's no requirement here that A be seen as a precedent, or that A change anybody's moral or pragmatic attitudes—only that it lower certain costs, in this instance by giving the government information.

[ … ]

Slippery Slope June: Cost-Lowering Slippery Slopes

[This month, I'm serializing my 2003 Harvard Law Review article, The Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope; in Wednesday's post and yesterday's post, I laid out...